In the community of Siempre Viva a large cloud of smoke appears that begins to disperse and obscure the area’s natural landscape. The Río Indio gradually becomes cloudy and stops reflecting the typical sun of summer in the municipality of San Juan, Nicaragua. On 3 April 2018, an alert from the Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities informed us of a forest fire in the Río San Juan Wildlife Refuge that would rapidly move towards the core area of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve.

From this moment on, public alarm arose over what was happening in this area, far from the Nicaraguan capital. Media and social media began to communicate the news. Nobody knew that we were facing an event that would change our country’s history. The hashtag #SOSIndioMaiz began to go viral throughout Nicaragua. It was like the awakening of citizen environmental awareness.

The fire was of great concern for three reasons: first, because the forest in the area had suffered the impact of Hurricane Otto in November 2016, which left a lot of fallen vegetative material; second, because we were in the dry season, when temperatures rise and there is less frequent rain; and third, because winds were constantly fanning and rapidly moving the fire towards the interior of the reserve. In other words, it was the perfect storm for a fire to spread and turn everything in its path to ash.

The Fundación del Río began to publicly demand state action to attend to this emergency and to declare a yellow alert in order to have all necessary capacities to stop the advance of the fire. The state’s initial response, however, was silence, denial, and a minimisation of what was happening. This outraged the capital’s young university students, who took to the streets to show their disapproval of government neglect.

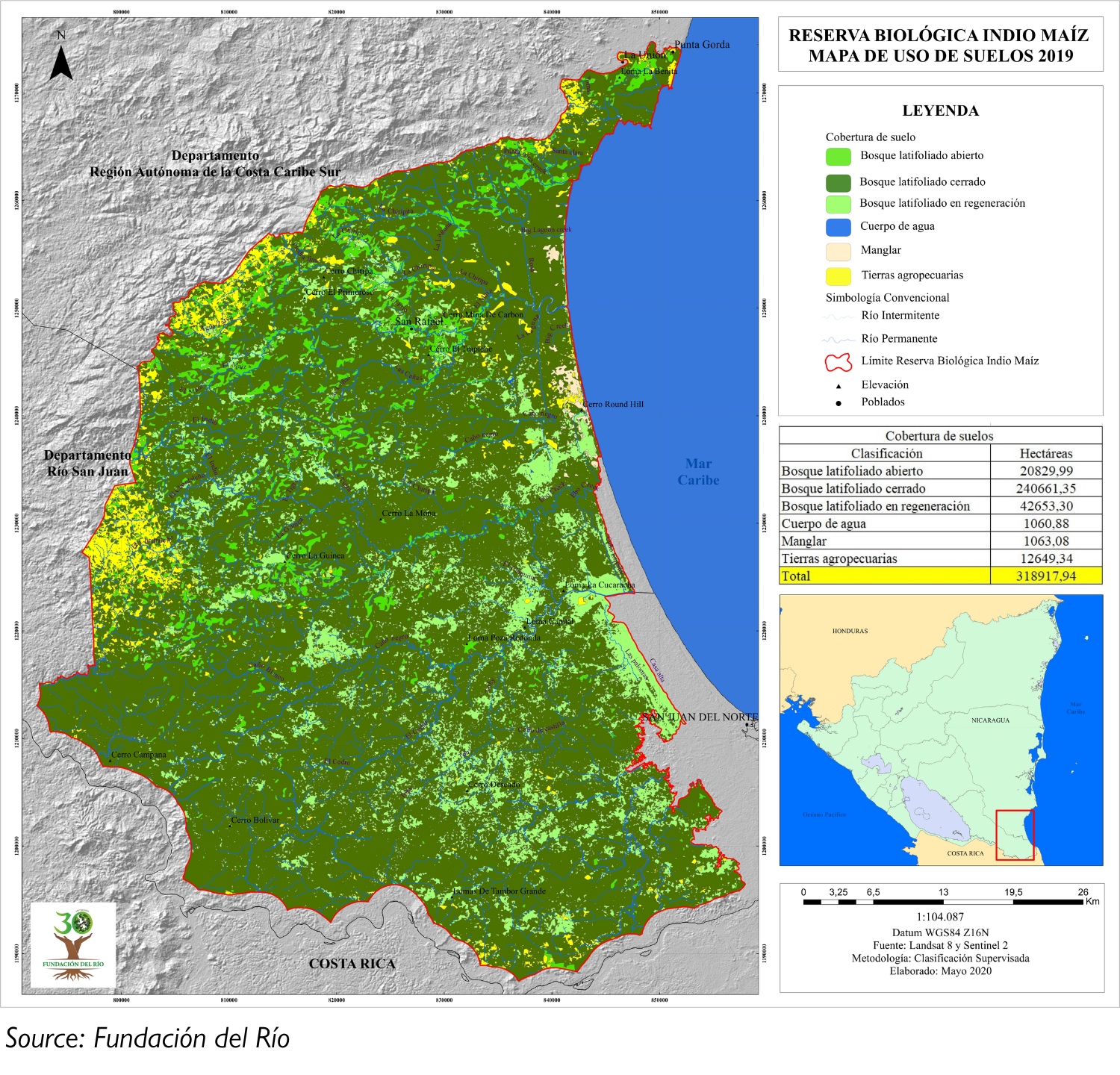

In the years before the fire, alarm had already been raised about the deteriorating situation in Indio Maíz, the second most important forested area in the country with 2,639 square kilometers, almost the size of the city of Madrid, Spain. Complaints about the invasion of settlers (invaders), land trafficking, deforestation, livestock, gold mining, and the construction of infrastructure were positioning themselves in the consciousness of the Nicaraguan population thanks to the diverse voices of the Rama Indigenous peoples and Kriol Afro-descendant communities (owners of 70% of the reserve), and local environmental organisations working in the area.

For this reason, when the first protests by young university students began in Managua, other societal groups came together in the streets, in such a way that the feeling of repudiation radiated in other cities, such as Matagalpa, where organised youth also protested. The government’s response to these demonstrations was violent and aimed to silence the demands of these groups through harassment and repression carried out by mobs linked to the party in power, forming part of the immediate antecedents of the socio-political and human rights crisis that we are experiencing in Nicaragua.

While this was happening more than 400 kilometers away from the fire area, the risk developed of losing the enormous biodiversity in Indio Maíz. The reserve is home to about 369 plant species and about 550 species including amphibians, reptiles, mammals, birds, and insects. Much was to be lost in an area that is part of, and connects, the Central American and Mesoamerican Biological Corridor. The government had no choice but to acknowledge, albeit belatedly, the emergency situation in the area, all thanks to social pressure and the advocacy of environmental organisations that demonstrated the fire’s advance on satellite maps.

During those tragic days of April 2018, the mobilisation of Nicaraguan Army brigades to the area was not enough to stop the spread of the fire that crossed rivers and ecosystems, drastically changing the existing green landscape. National capacity to tackle the fire was very limited; the country had not invested in preparations for this type of event. For this reason, the public call of #SOSIndioMaiz was made to ask for solidarity and international support. Several countries answered this call, including Costa Rica, mobilising a specialised forest fire unit. However, on 9 April, the Nicaraguan government rejected the collaboration offered by Costa Rica to fight the fires, again fueling the population’s social discontent.

Even though delayed national efforts and international solidarity helped neutralise the fire, it was not until 16 April 2018 that Mother Nature sent enough rain to eliminate the last strongholds of the fire in the area. The fire burned some 6,788 hectares of humid tropical forest and Yolillal ecosystems. The presumed origin of the forest fire was determined to be uncontrolled agricultural burning by a farmer who was allegedly illegally occupying part of the Indigenous and Afro-descendant territory, a phenomenon that, since 2009, has been intensifying, according to the Rama and Kriol Territorial Government.

Three years after the fire, the deteriorating situation of the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve continues, and while the government made an “urgent call to preserve and recover forests as the best way to face climate change” during the Climate Vulnerable Forum on 2 November 2021 at the COP26, Nicaragua is the country with the fastest deforestation rate in the world. In the Indio Maíz Reserve, denouncements of invasions, gold mining, and the advance of livestock areas within its core area are a daily occurrence. The last map made by Fundación del Río shows that in 2020, 23% of the forest was deforested, degraded, or in natural regeneration. However, 76% of the forest is conserved, thus keeping alive the hope of continuing to fight for this important natural reserve, as well as of maintaining the spirit of environmental awareness that was awakened among citizens in April 2018.

The Nicaraguan state’s repression of land and human rights defenders has positioned the country as the deadliest in the world per capita for the defence of the environment and land in 2020.[13] The model of criminalisation used against environmental rights defenders in Nicaragua is repeated in many countries, where raising one’s voice means exposing oneself, or even having to move or go into exile to protect one’s physical integrity. We must continue to denounce the governments’ actions on environmental matters and contribute to creating a context for just development so as to avoid ongoing adverse impacts on ecosystems, territories, and communities.

Amaru Ruíz Alemán | Fundación del Río

[Photo: Otto Mejia]

This article is part of PBI Nicaragua in Costa Rica's publication “Nicaraguan voices in resistance”, a project that unites different voices from Nicaraguan exiled human rights defenders. It is a tribute to the Nicaraguan organisations and collectives that, from exile, work continuously in the defence of human rights, bringing together the voices and testimonies of those who promote this work through non-violent action and in a culture of peace.